Can the sad tale of the Asian arowana have a happy ending?

Abundant in farms and prized in the aquarium trade for decades, the famous freshwater fish is still waiting for conservation benefits to materialise.

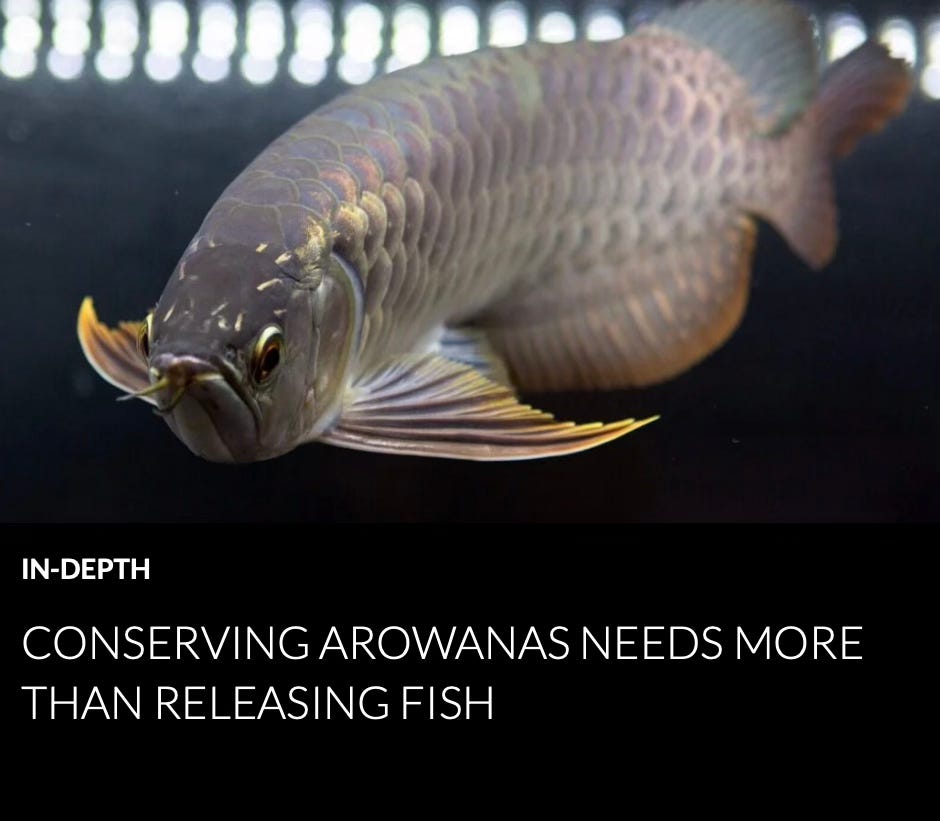

For aquarium hobbyists, the Asian arowana needs no introduction. The species is one of the most expensive fishes in the aquarium trade, with millions sold globally since they caught the eye of hobbyists over half a century ago.

Asian arowanas are plentiful in the many farms that breed them to meet hobbyists’ demands. Yet in the wild, the fish appears to be barely holding on.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature assessed the Asian arowana as endangered in 2019, concluding that:

The population of this species is at very low densities throughout its range following significant declines in the past.

Over recent months, I’ve been looking into the Asian arowana’s story with Malaysian journalist Yao-Hua Law. Malaysia is the top global exporter of the fish, with Indonesia following closely behind.

This has culminated in an in-depth, two-part series published by the environmental news site Macaranga, which Yao-Hua co-founded.

As aquatic ecologist Fatimah binti Yusoff of Universiti Putra Malaysia says in Part 2 of the series, “Arowana is a sad story.” Like this reporting, the fish’s tale can be told in two distinct parts.

Firstly, the Asian arowana suffered unsustainable exploitation in the wild from the early days of its popularity in the aquarium trade, as the IUCN assessment suggests. With the species’ populations declining, the newly established Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) chose to list the species on its Appendices in 1975.

CITES regulates global trade in the threatened species on its lists. For the Asian arowana, this means that international commercial trade in wild-sourced individuals has been largely forbidden since the mid 1970s.

This brings us to the second part of the arowana’s saga. Following its CITES listing, people discovered how to breed the fish in captivity. The Asian arowana trade has since grown into a multi-million dollar business, as CITES allows these farmed fishes to be bought and sold globally, subject to certain requirements.

But what of wild arowanas? As Part 1 of the series notes, while the farmed arowana business blossomed, “wild arowanas faded from public attention. Virtually nobody championed their protection.”

There have been limited releases of farmed fishes in Malaysia in recent years to try and bolster numbers in the wild, with perhaps more of these to come. Several experts told us during the course of reporting that such releases need to be done with extreme caution, to avoid issues like genetic pollution and disease risk.

Meanwhile, any arowanas – and other aquatic species – living in the wild have to contend with habitat-related threats due to development.

To sum up, the various stakeholders involved – an international treaty body, governments, the aquarium industry – have secured an enduring trade in Asian arowana but not (as yet) a prosperous future for the fish in the wild.

However, despite their present predicament, if arowanas are afforded staunch legal protections, their habitat conserved, and scientifically robust releases are initiated where appropriate, “there is hope.”

As the series says, “We have the time and words to write a happy ending for the Asian arowana story.”

Although the Asian arowana’s story is unique to the species, similar tales can be found across the world.

For instance, the Danube sturgeon (also known as the Russian sturgeon) and Siberian sturgeon are both critically endangered in the wild, yet there is a thriving trade in products from captive-bred animals, particularly luxury caviar.

It is illegal to internationally trade wild sturgeon caviar, as a 2023 study highlighted. WWF has explained that this is because “international trade from all major stocks has been suspended since 2011.”

However, the study’s authors – a group of sturgeon experts – tested 149 samples of caviar and meat from Eastern European countries to determine their source. The probe showed that trade regulations “are actively being broken”. The team found that around half of the tested products were illegal, either because they were derived from wild sturgeon or violated CITES and EU rules in other ways.

In other words, the existence of a legal trade in products from captive animals is providing cover for illegal activity that puts wild sturgeons further at risk.

To sum up, although trade in captive or semi-captive species may benefit wild populations in some instances, much work remains to be done to ensure that this is the case across the board.

For the world to tackle the worsening extinction crisis, in which humans’ use and trade of wild species plays a central role, regulatory inadequacies like this need to be urgently addressed and resolved.

If you would like to see more of Macaranga’s environmental reporting or become a supporter of its work, head over to its website here.